(Originally published September 19, 2013 in East Bay/South Coast Life)

From where I’m sitting, if I turn my head 90° to the right I have a view of a butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii ‘Ellen’s Blue’) planted under my window. I can clearly see, even through the screen, the tiny orange anthers inside hundreds of deep purple-blue flowers clustering every twig end, and my nose is filled with its honey scent whether I’m looking at it or not. But what I cannot see are all the butterflies that give it its common name.

Over the course of the summer I haven’t seen many Black Swallowtails, though I have spotted their caterpillars munching my bronze fennel and dill. Last year every anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum and cvs.) was visited by dozens of Painted Ladies. This year, not a one. I haven’t seen any Red Admirals either. And the most iconic of all, the butterfly whose inconceivable migration to and from a pin on the map of central Mexico has captivated us all since childhood, is conspicuously absent.

I can count on one, maybe two fingers how many Monarch butterflies I have seen so far this year, and they weren’t even in my garden. I’m not alone. My in-laws, who spend their August vacation way up in the nosebleed section of Ontario, Canada enjoy watching whole flocks bask on Lake Huron’s rocky outcrops. The butterflies were a no-show this year and other friends, closer to home, are reporting similar news. It’s not OK. The Monarch’s absence has been especially distressing to me because I allowed the milkweed in my front yard garden to proliferate madly.

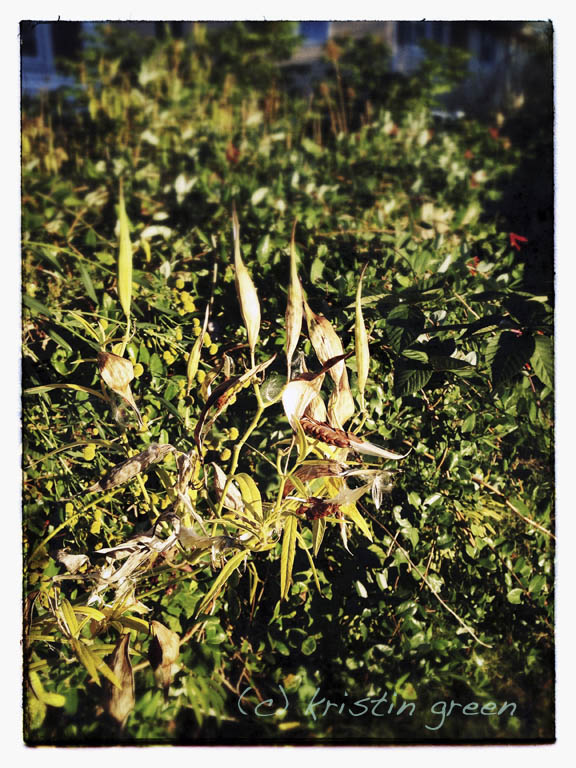

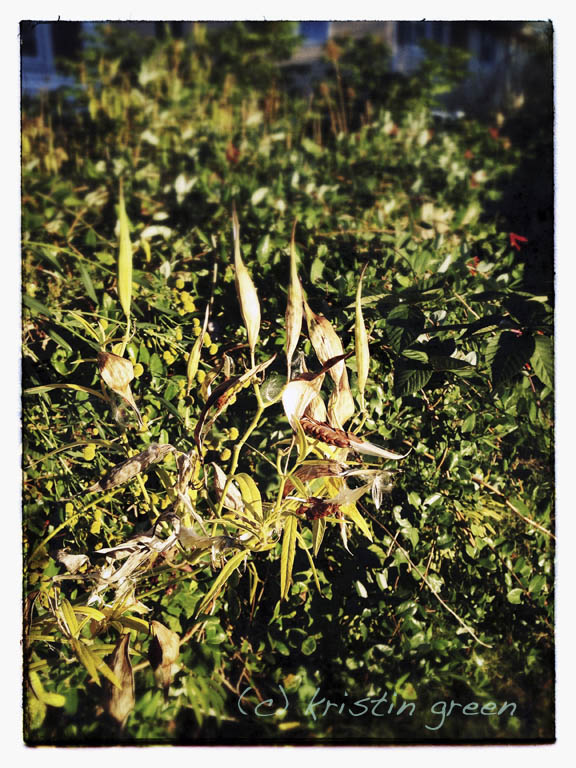

I’ll admit that wasn’t entirely intentional. Every fall I scatter seeds stolen from butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), a sturdy two-footer with clusters of bright orange lunar lander flowers. This past spring, when I saw the telltale pointed leaves rise on milk-sapped stalks, I thought this is it! They’ve taken. Alas, when the plants rose another foot or two and opened clusters of Pepto-pink and creamy-white flowers instead, I had to concede defeat. But all was not lost because swamp milkweed (Asclepias elegans) and its white cultivar ‘Ice Ballet’ are just as garden worthy and evidently perfectly happy to spread in my stony soil. Plus, they too are an essential food source for Monarch butterfly caterpillars. So I let broad swaths crowd less important plants out.

I’ll admit that wasn’t entirely intentional. Every fall I scatter seeds stolen from butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), a sturdy two-footer with clusters of bright orange lunar lander flowers. This past spring, when I saw the telltale pointed leaves rise on milk-sapped stalks, I thought this is it! They’ve taken. Alas, when the plants rose another foot or two and opened clusters of Pepto-pink and creamy-white flowers instead, I had to concede defeat. But all was not lost because swamp milkweed (Asclepias elegans) and its white cultivar ‘Ice Ballet’ are just as garden worthy and evidently perfectly happy to spread in my stony soil. Plus, they too are an essential food source for Monarch butterfly caterpillars. So I let broad swaths crowd less important plants out.

If only the Monarchs were here right now to appreciate my generosity. But according to counts conducted annually in the Oyamel fir forests of Mexico, their population declined 59% from just last year. Since 1996-97 their winter range has dwindled from nearly 45 acres of forest to just under 3 acres. That is shocking. Deforestation within their refuge in Mexico is partly to blame as is the unseasonable weather during migration caused by climate change. But habitat loss on this side of the border has been particularly detrimental.

It is perfectly appropriate to heap blame on Midwestern farmers who spray weedkiller over their fields of genetically modified Roundup Ready® crops. But even though the corn belt is an important egg laying point for butterfly generations en route north, we are also to blame. In many yards and gardens milkweed is still considered a weed—as are many of the host plants for other species of Lepidoptera.

Insect populations typically cycle through highs and lows and so far biologists are not sounding the Monarch’s extinction alarm. But I hear a wake-up call. Everything on this earth is connected and the ripples from a drop fan out. The very least we can do is to remember that our gardens are a vital part of a struggling ecosystem.

It is so easy to attract butterflies to the garden. Winged adults feed on nectar and only require a smorgasbord of flowers. Most of us, we gardeners anyway, are more than happy to oblige. But to keep butterflies in our gardens, and to ensure generations of survivors, we absolutely must provide their eggs and caterpillars with the proper host species and—this should go without saying—a safe, pesticide-free habitat too. If you plant it, they will make a comeback.

Have you seen (m)any Monarchs this season?